It was an ill-fated flight that nearly didn’t happen for me. I was to lead a stream of aircraft at five-minute intervals on a night navex from Williamtown to Orange and Tamworth, returning to Willy over the Barrington Tops high country north of Newcastle. I was in A3-52, Jake Newham’s own mount, the Squadron flagship. She was just back from the mod programme at Avalon which incorporated ground map radar, doppler, radio altimeter, flying aids etc, just 50 hours on the clock. As a 22-year old Pilot Officer, I was impressed with my charge, and looking forward to the flight.

On start up, the alternator would not reset. We varied the RPM and the troops were busy underneath, but the ALT light would not go out. I was about to shut down when a Corporal electrician, Lindsay Ball I think, indicated he would go up onto the fuselage. Bob Walsh appeared from the crew room looking worried – what was the hold up! The equipment bay opened and Bingo, the light went out, I was on my way.

It was a cold, dark September night in 1967. There was a strong westerly blowing at 36,000ft on the final leg and the Mirage was revelling in the conditions. My doppler was giving me 600kts ground speed, the aids were flying the plane and I could see the base on the radar - the French Lady was bunging it on. Suddenly, without a sound, the engine quit, zero RPM, and the fail panel lit up like a Christmas tree, I could hardly believe my eyes!

I set up in a 300kt glide and put out a Mayday call to Willy Approach. At 25,000ft I tried a relight, which achieved nothing except dimming the cockpit lights. I started to consider my options, which were very few, when suddenly both fire-warning lights came on - later revealed to be a symptom of a flattening battery. Expecting the plane was about explode, my inevitable decision was made for me.

I pulled the face blind handle and the seat shot up the rails, tumbling backwards and stabilising with the drogue. There were several minutes of free fall, then to my great relief, the main parachute opened automatically at about 10,000ft. For nine minutes I swayed quietly beneath the canopy. I could see nothing below in the darkness, but I could feel the air getting warmer and I could smell the earth coming up, it smelled like… cow manure.

I hit the ground like a bag of spuds, falling backwards and banging my head. There was no wind so I lay there looking up at the stars, my heart pounding – I think it’s all over.

I was very fortunate to have come down onto a cow paddock and not into high trees. I made my way down a roadway and was soon overflown by a Neptune, scrambled from the circuit at Richmond. The Neppy orbited over my beacon and I fired a flare to acknowledge.

I came to a farmhouse and knocked on the door. An old man appeared, come in, he said, I’ll put the kettle on. He had been contacted by the local police to be on the lookout for a downed pilot, otherwise he may have gone for the shotgun; dressed in G suit and Mae West, and with a wound on my neck from the face blind, I must have looked…alien.

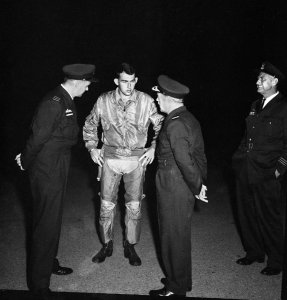

After what seemed to be an eternity to me, a Police Land Rover arrived and I was taken to the Gloucester show grounds where a RAAF chopper waited. The whole town, and the media, was out for the occasion.

As the Huey thumped it’s way back to base through the darkness, the drama of the event started to sink in to me. I was very remorseful that I was not able to bring that fine machine back to its home. I was angry that some component had let us down, and I wanted to know what had gone wrong. But I was grateful to be alive, and most thankful to Mr Martin Baker and the troops who serviced his equipment - the seat worked perfectly and certainly saved my life.

We searched the area for weeks with a fleet of choppers, but found nothing. The old man in the farmhouse had heard that there was a reward for finding the wreckage. He thought he heard the thump of the aircraft hitting the ground, and being an experienced bushman, he would go out on a different radial each weekend searching over a period of twelve months. One day he walked into a crater and kicked a bit of tin with Mirage written on it. Unfortunately, there was no reward, so we paid him a visit and presented some squadron merchandise.

Excavators were sent to the site, and started digging. They got to the engine nozzles, the rudder, the mainplane and eventually the bit they wanted at the front of the engine. Components were analysed at CAC in Melbourne and revealed that the engine gearbox bearing had seized from lack of lubrication thus shearing the Drive Bevel Gear causing engine flameout. Further inspection discovered fragments of rubber and wood blocking the oil line. It is possible that these foreign objects were part of a bung used to keep oil lines clean during the aircraft’s manufacture.

The RAAF subsequently modified the Atar engine to incorporate a filter in the oil feed pipe and added an extra oil jet to the gearbox. No further such failures occurred in RAAF service.

the 10 Dec 23. Marty Susans. Mirage Ejection Statistics. document